WaterAid has commissioned 10 visual artists from across the Global South to interpret the far-reaching impact access to clean water and decent sanitation has on people’s lives and the role these vital basics play in the realisation of other human rights.

The thought-provoking collection was released on 28 July 2020 to mark 10 years since water and sanitation were recognised by the United Nations General Assembly as vital human rights, which should be afforded to every person.

Over the last 10 years, millions have gained access to clean water and decent toilets and close to half of the world’s developing countries have amended their constitutions to include water and sanitation as human rights.

But there is still a long way to go. Globally, 785 million, that’s 1 in 10 people, still lack access to clean water close to home and 2 billion – 1 in 4 people – don’t have a decent toilet of their own.

International charity WaterAid is using the striking new images to highlight its call on governments around the world to double their investments in providing clean water and good hygiene to those most at need in response to the COVID-19 crisis, and in turn help improve the health and prosperity of whole communities.

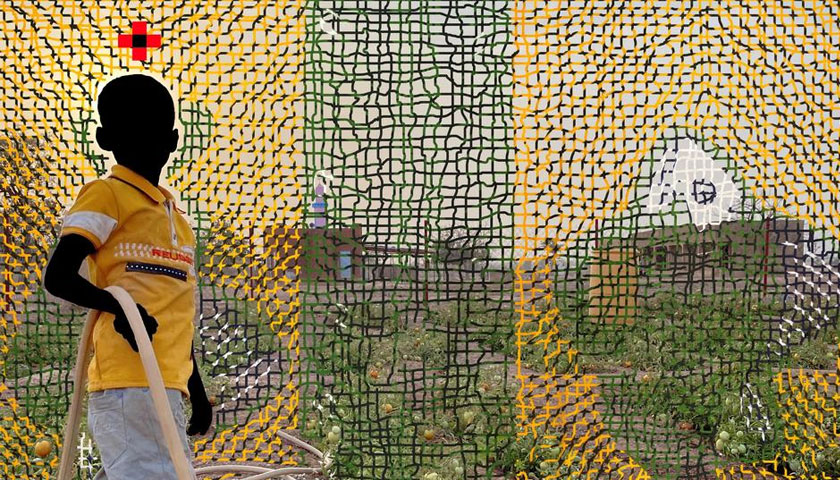

Serge Attukwei Clottey is a Ghanaian artist who works within installation, performance, photography and sculpture, using found and recycled everyday objects. He produced an image using the yellow plastic jerry cans people use for collecting water in Ghana, where 1 in 5 lack access to clean water. He is passionate about exploring attitudes to climate change in Ghana. He explained:

“In Ghana, the streets are filled with children carrying yellow buckets on their heads, on their way to a fountain…. Every day I would see women and children pour in by the hundreds.

“I want this photo to demand social justice by exposing environmental problems in today’s society. It inspires the human spirit by calling people to action.”

Spanish documentary photographer, Cristina de Middel, who lives in Bahia, Brazil creates fictional scenes based on reality in her photographs. Her image explores the idea that there can be water everywhere, but that this doesn’t translate into water access for the community:

“I wanted to reflect on the fact that the abundance of water does not necessarily mean the quality of water. I live in a small town in the state of Bahía (Brazil) and we are in the middle of the rainy season. There is water everywhere, but it rains with such intensity that the water system collapses very often and there is no water at home.

“We just walked to one of the many streams and sources of water there is around with a few ideas in mind and played with the different possibilities.”

Poulomi Basu is an Indian transmedia artist, photographer, activist and author. Her work as a human rights activist explores the taboos surrounding menstruation and violence against women. She has worked with WaterAid previously to highlight the ways in which lack of access to water, sanitation and hygiene impacts women. Poulomi’s piece is a take on the iconic photo of photographer Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, and is a reflection on the many people who take easy access to water for granted – despite the fact it is something millions of women live without. Poulomi explains:

“The water in the bath tub [is] blood red: a symbol of menstruation. I have kept the boots, but added a bucket, a symbol of the great distances the many women around the world must walk to fetch water, or to find the seclusion of a forest, so that they can go to the toilet.

“I’ve replaced the photo of Hitler with ‘Anjana, a 12 year-old child bride, Nepal’ from my series, ‘Blood Speaks’, to reframe this image in the shadow of all of those who live without adequate sanitation, and systems of blood politics and control, which are often connected.

“I hope that this image makes people reflect on the easy access we have to water and sanitation, and how for so many women and girls across the world, this is simply not the case.”

Multimedia artist Joseph Obanubi, who is based in Lagos, Nigeria, also chose to focus on the impact a lack of access to clean water can have on women and girls, who are responsible for water collection in 8 out of 10 households with water off premises. Joseph also created a second piece, which highlights the risks of open defecation:

“For many communities, water sources are usually far from their homes, and it typically falls to women and girls to spend much of their time and energy fetching water, a task which often exposes them to attack from men and even wild animals. Without improved sanitation – a facility that safely separates human waste from human contact – people have no choice but to use inadequate communal latrines or to practise open defecation. Finding a place to go to the toilet outside, often having to wait until the cover of darkness, can leave them vulnerable to abuse and sexual assault.

“[The work] dabbles into spirituality, functionality and gender, referencing Nigerian-Yoruba sitting sculptures with the poses. It dwells on the healing qualities of water as an integral part of a things. Water is a basic element of life and an essential factor in the Yoruba religion. Yoruba believe water to be a symbol of force and strength.”

Dafe Oboro, also based in Lagos, documents the city’s youth communities through film and photography. Dafe has created a piece which focuses on the daily ritual of bathing, and his image depicts an abundance of clean water.

“Pour me Water, Pure Water presents one idea – bathing as an essential everyday ritual. This serves as a tribute to local workers around me here in Lagos, from the mechanics to the plumbers and the bricklayers who I see taking their baths, with their shorts on, behind parked buses.

It is evident that without such right, a ritual as simple and important as bathing would be impossible. In the end, water is life.”

Collin Sekajugo is a Ugandan multidisciplinary artist living and working in Rwanda and Uganda and has created a piece titled All on Her. He described his piece, which depicts a young woman carrying jerry cans:

“I have always found the jerry can to be such a symbolic item in African homes. In almost every community it’s used for trading consumer commodities… most importantly it’s commonly used for fetching and storing water. I have grown to believe that a home without a jerry can is unliveable.

“This artwork speaks to the symbolism of a jerry can versus its importance in accessing clean water and observing sanitation.

“[It] is dedicated to all the women and children – especially young girls – who, on a daily basis, walk miles in search for clean water to sustain their families’ wellbeing.”

Also featuring in WaterAid’s collection are:

Saidou Dicko – a self-taught visual artist, photographer, videographer, installer and painter from Burkina Faso; Henry J Kamara – a British-Sierra Leonean artist, photographer and story teller whose works tries to understand what it means to be an African in the diaspora; British-Mexican multidisciplinary visual artist, Monica Alcazar-Duarte and Giya Makondo-Wills, a British-South African documentary photographer selected as one of ’31 women to watch out for’ by the British Journal of Photography.

Find out more about WaterAid’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and their work to bring clean water and good hygiene to everyone, everywhere here.